Even the simplest tasks seem daunting when you experience burnout, stress, or long-COVID.

Your words feel jumbled up in your brain, and the idea of being hyper-productive in your pre-COVID setup seems terribly unappealing.

Whenever you got behind with a project, you’d sacrifice some sleep and burn the midnight oil. And even if the stress piled up, you’d push through.

But what if you can’t sacrifice family time and sleep to get things done? What if your health won’t allow it? I had to reevaluate my systems and relationship with work in light of mental fatigue and burnout.

If you’re a creative, a communicator, a student, or a white-collar worker who deals with brainwork instead of physical work—this article is for you.

How your brain processes information

We use our senses—sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch—to take in information from the environment: your fingertips on the keyboard, the smell of coffee, your coworker’s phone vibrating across the cubicle, the fresh mint in your mouth, the temperature that’s just right, that loud notification ping, the flashy light, the technicolor screen, etcetera. These are stimuli, or impressions.

These impressions linger in our sensory memory from 0.5 to 10 seconds. If your brain deems any of these important, it will pay attention and place the particular input in your working memory or short-term memory.

If you keep engaging with the information, your brain will encode it into your long-term memory. If not, it will eventually fade from your short-term memory.

Your long-term memory is like a repository of knowledge structures called mental schemas (or schemata). A mental schema is a pattern of understanding and reasoning.

For example, you have a mental schema of a ‹dog›. It might look like this: a furry four-legged pet that barks, a loyal and protective domesticated animal, a man’s best friend.

Now, this schema of a dog is quite automated: you don’t think hard to conjure the image of a dog in your head. You know how it barks, looks, smells, etc., because you’ve gathered a lot of input throughout the years.

Golden retrievers, beagles, huskies, and poodles are kinds of a ‹dog›. A fox is not a ‹dog›. A wolf looks like a ‹dog›, but it’s still not a ‹dog›.

Note: if you find Cognitive Linguistics remotely interesting, read George Lakoff’s Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things for a non-academic journey into language and cognition.

So the image of a dog is deeply entrenched in our minds.

But if you read last month a behavioral fact about dogs that you haven’t reinforced in your working memory—that is to become part of the mental schema of ‹dog›—then chances are you have already forgotten it or will soon forget about it.

But why do we remember some input and not others?

It’s because of the inherent quality of the information. Let’s explore this from a cognitive standpoint:

What is cognitive load

Remember how I listed all those impressions in your office environment? I just pointed out a few blatant ones.

And for good reasons, too. Can you imagine if you were to take in every single bit of information? You’d feel overloaded.

All sensory input is taxing for the brain, so your brain chooses to focus on a select few, between 3 to 7 pieces of information.

This is called a cognitive load, i.e., how much information your working memory can hold at a given time.

Note: Educational psychologist John Sweller developed Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) based on his observations of how students absorb and retain information. Start reading here.

According to John Sweller, there are three types of cognitive load:

- Intrinsic cognitive load – how complex the new information is. Remembering what a dog looks like or the name of the dog’s breed is one thing. Studying dog behavior (cynology and canine ethology) is another. Some things are intrinsically easy, like basic math (1+1=2), while calculus is difficult because it is built on various complex knowledge structures.

- Extraneous cognitive load – how the new information is presented to you. For example, reading the definition of a poodle—“any of a breed of intelligent dogs that have a curly dense solid-colored coat and that are grouped into standard, miniature, and toy sizes which are often considered separate breeds”—is more mentally taxing than looking at a picture on Google Images. Also, if you wanted to teach your dog new tricks, would you look up instructional images in a book or watch a Youtube video? Probably the latter.

- Germane cognitive load – how the new information connects to prior mental schemas. Germane means “closely related” or “relevant.” It’s the deep processing of new information by integrating it with learning. Here’s a simple example: you’re reading about the Akita breed (or Akita Inu), and you remember you saw one yesterday in the park. What you read reinforces your understanding that dogs (e.g., retrievers) are loyal, just like the touching story of Hachiko. You’ll also find it easier to distinguish it from its kin, the Shiba Inu, who has a rather foxy look—still not a fox—and is more stubborn, yet unrelatedly, it is the name of the dog-themed meme coin.

Now, if you have to write a paper, essay, or short story on dogs, you’ll at least have a point of reference and solidify or create other mental schemas as you dig deeper.

By the way, writing is one example of a high-cognitive load task because you need to process a lot of sensory input and transmit it from working memory to long-term memory.

Takeaway: for your brain to work optimally and efficiently, try to:

1) simplify the intrinsic load

2) reduce the extraneous

3) maximize the germane

The (obvious) problem with burnout

“OK, but what does all this have to do with work, task management, and how fatigued I am?”

Burnout and mental fatigue take a toll on your cognitive functions.

- Sensory memory is affected.

Sensory memory lingers and loads your brain even more when you’re burned out or stressed out. You wouldn’t care about background noise on a good day, but you find it incredibly annoying when you’re tired.

On a typical day, you wouldn’t stress about a pile of documents next to your keyboard. But on a deadline, it feels like that pile is hanging over your head, stressing you out even more.

To compensate, your brain will tune out certain stimuli, leaving you aloof, distracted, or confused. This might feel very similar to brain fog, an intricate and sensitive topic I won’t delve into.

- Working memory is affected.

When your mental energy is depleted, you will find it hard to focus. So, an easy task is suddenly more difficult (intrinsic cognitive load), and you need more straightforward means to process it (extraneous cognitive load).

For example, in a conversation, you’ll ask the other person to speak more slowly or ask them to repeat what they said, especially when explaining a task. Just like when you’re watching a movie, and you’re tired, you’ll switch on captions or subtitles, even though it’s your native tongue.

- Long-term memory is affected.

What’s more, that simple task you once finished quickly takes longer because you’re too mentally drained to learn and process new information (germane cognitive load), especially if you’re working in creative fields.

Sometimes, you feel like you can’t be bothered to come up with a better idea, or worse, you feel like you can’t.

When working memory is affected, it will put you in a bad mood. You can’t access the information you used to retrieve so quickly, from names to words and definitions, fun facts about your close ones. You’ll feel frustrated and want to give up. You’ll have to think long and hard about that touching story of the loyal dog—what was its name again?—and hope it’ll come to you.

If that happens once in a blue moon, it’s fine. But what if it’s been your daily default for the past months?

Fear not.

I can’t stress enough how important sleep and relaxation are. Nutrition, sleep, and exercise will help. Medical help may be in order.

It will take some time to recover from burnout. If you can take time off, do so.

Until then, you’ll have to work on how you work—pun intended.

How to lessen your (mental) workload:

One more thing you can leverage? Task management for health’s sake.

Here are some short-term adaptive strategies to manage everyday tasks as you are getting enough sleep, eating well, exercising, and focusing on your health.

These are not steps per se—so you don’t need to do them sequentially—just things you could ease into and refine for better mental health.

1. Start small

Highly-productive individuals do experience burnout and increased cognitive load. They take an extra blow in their confidence and get frustrated if they can’t sustain their former pace: “I used to finish the first draft in a few hours, but now it takes me a whole day for an outline.”

Start small and pace yourself.

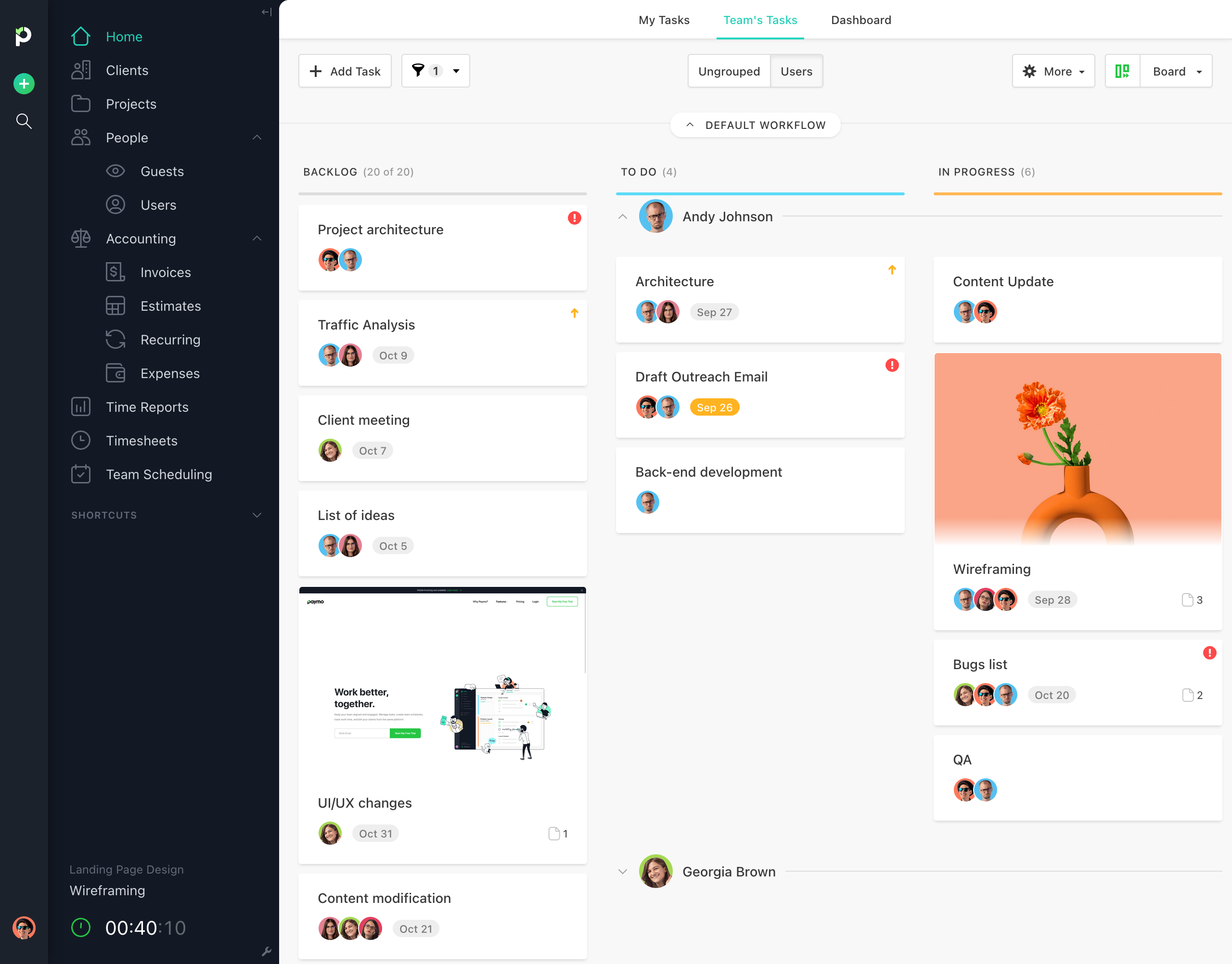

In Kanban methodology, limited WIP (Work In Progress) helps you keep an optimal pace.

If you limit your WIP to three or four, you’ll avoid multitasking and won’t feel overwhelmed. Make the tasks granular to avoid cognitive load.

Set the success bar low. If you made significant progress or finished at least one task, count that as a success. Keep going.

2. Space out your work

To avoid task-switching, I would focus on just one project at a time. “I’ll start working on the next project after I finish this one.”

Let’s say you’re making a video essay on Villeneuve’s Arrival. You’ll need a time estimate on your creative project:

- Watch the movie — 2h

- Take extra notes + select three key scenes — 1h

- Write 2,000-word script (ideation, writing & editing) — 12h

- Record voice-over — 2h

- Video production — 8h

- Finishing touches + float — 5h

That’s 30 hours of creative work. Back in the day, I used to cram everything over the weekend—start working on my project on Friday afternoon and finish it by Sunday night with some sleep in between.

I thought that’s how I kept my head in the game – being creative, diligent, and not losing focus. Well, that pace was unsustainable and reminded me of my college days.

After having experienced mental fatigue and long-COVID, this work regimen was no longer feasible.

This tip might sound uncomfortable for those of you working in long, uninterrupted sessions:

Space out your work across projects throughout the week.

“Hold on, won’t that make me unproductive with all this multitasking?”

It’s not multitasking but a coarser timeboxing strategy.

Nowadays, I’m more productive working on my projects parallelly rather than sequentially. I no longer wait to finish project X to start working on project Y. I try to make minor, consistent progress across multiple projects in a week.

3. Declutter

Digital clutter increases your cognitive load.

What we experienced during the lockdown in 2020 was that calendars and task lists could be wiped clean, which was scary but liberating.

Having learned that, I did something quite bold—crazy even—this summer: I purged almost all lists, bookmarks, to-dos, and notes I amassed over the years.

My backlog of personal projects needed a clean slate. I got in this messy state because I always stopped at “Capture,” the first step in the Getting Things Done methodology.

Now I think twice before I bookmark research for later. Plus, I’m developing a better system for keeping notes built on the Zettelkasten.

I’m not saying you should be this radical. But try to subtract from your workload. What can you cut altogether?

I set deadlines for my ideas, like an expiry date. I list them as tasks in Paymo. For example, I found out I was 420 days late on an “idea,” so I resolved not to do it because—if I were honest—it had no real utility.

Action steps: purge or subtract tasks. Set deadlines for your ideas.

4. Delegate

Delegating helps declutter your task lists, as explained in this article on the Eisenhower Matrix.

In a nutshell:

- Train a subordinate considering the 30x rule.

- Hire an assistant.

- Find collaborators.

I’ve been dallying with the third idea, and so far, I’ve found the collaborative process rewarding.

5. Start saying ‘no’ more often.

Time is a limited resource. For every committed ‘yes’ here, there has to be a straightforward ‘no.’

But in light of mental fatigue, double down on saying ‘no’ at least short-term. Most people will understand.

I’ll refer you to this lovely article on 50 ways to nicely say no.

6. Prioritize

When you prioritize a task as ‘urgent’ or ‘critical,’ it tricks your brain into a higher cognitive load mode.

While there are methods to prioritize, from the Decision Matrix to the MoSCoW Analysis, I keep it simple. I choose one task and assign it a higher priority. I know that’ll be my ugly frog for the day.

So, if you have a 3-task WIP, one is your critical task. The other two are probably a part of different projects—for the sake of working parallelly.

7. Work in fixed sessions

This strategy is similar to time blocking and its offspring – timeboxing, day theming, and task batching.

It’s nothing new under the sun, just a reminder to follow your natural rhythm to perform those highly demanding tasks when your brain has the energy for the highest cognitive load.

Similar to Oliver Burkeman’s four-hour working day, Carey Nieuwhof’s Green-Yellow-Red Zones is a simple way to visualize your day in energy dips and peaks:

“Think of your peak 3-5 hours as your Green Zone—when your energy, focus, creativity, and great ideas flow easily and sharpest . . . Your Red Zone is the opposite—it’s those 1-2 hours when you’re dragging, need caffeine to stay awake, and can’t focus deeply on anything—sometimes you struggle to produce any meaningful work . . . Your Yellow Zone consists of the hours in between—you are neither at your best nor your worst.”

How my work session looks like nowadays:

- I jot the task down on a sticky note or desktop sticky. One line. I use it to refocus when I get distracted or after I take a short break.

- I put it in my task list, Kanban, or Calendar. It’s usually a detailed task in Paymo with subtasks as logical steps.

- I use a (Pomodoro) timer. I never work without a timer. Even if it’s a non-work task, I keep track of my time to keep me grounded and fine-tune my time perception.

I could write an ode to the Pomodoro technique, but I’ll spare you the lyrics. Use a Pomodoro app to augment your work and review your time entries at the end of the week.

Paymo’s Pomodoro is great as it logs each time entry yet prompts you to take a break.

This leads me to #8, my favorite tip to share and my epiphany of 2022:

8. Be ruthless about stopping

What do you do about those highly productive work sessions when you get into that flow state and feel you could push for another hour or two?

You stop.

You don’t want to return to the hyper-productive, rapid-fire pace that’s no longer sustainable, right?

It’s not about pushing yourself harder but knowing when to stop and recover despite the unfinished work.

If you tend to binge-work—in contrast to deep work—try this liberating yet counterintuitive hack.

Monks work only three hours at a monastery in New Mexico, ending at 12:40 pm. In his book, The End of Burnout, Jonathan Malesic interviewed monks about work, rest, and productivity.

When asked what you do when you feel that there’s still work left to do, you’re being unproductive by not working hard enough? The answer was, “You get over it.” Rest.

Work is not an endless activity on a continuum.

9. Have touchpoint meetings

When I started delegating more in my projects, I found that those 1:1s with my “collaborators” (read: friends or mentees) were immensely productive.

It helped me break down my workload as I managed theirs and held me accountable regarding deadlines or dependencies.

A touchpoint meeting at work would be a 10-minute conversation in which I ask questions or clarify the first step of a more complex task.

I’m transparent about where I’m at, giving me the impetus to start working on it.

10. Reconsider your calendar

Purge your calendar if you can, and take a raincheck—most people will understand!—and add as much float as possible. Knowing you have some slack in your schedule will take some of that pressure off your chest.

A more straightforward rule of thumb:

Don’t cram, but spread out tasks and events.

If your social energy depletes quickly, resolve to one weekly social event. Start small, then add them as you see fit.

11. Take breaks

Some people find the Waking Rest-Activity Cycle productive, which means you work for 90 minutes, then rest for 20.

My revised system is yet to be iron-clad. Assuming I’m in my Green Zone (see tip #7), the structure of my work session is this:

- Hard task.

- Break.

- Bundle of manageable tasks.

- Break.

- Hard task.

I found that my energy depletes more quickly, so I’m more intentional about taking breaks (see tip #8).

When I get stuck or need a break, I bundle tasks as part of a more extended Pomodoro break. I set the music for 15 minutes, organize my desk, vacuum my room, or wipe the floor for a more energy-intensive activity.

I do manual tasks after a session of brainwork.

If you tend to procrastinate like me, don’t “relax” by doing something mindless, like scrolling social media or watching videos. Find a quiet place to sit. Lie down for five minutes. Take a walk. Brew a cup of tea. Try not to read—especially if it’s part of your job—unless you find it satisfying and relaxing and can mentally distinguish it as a break.

12. The 5-4-3-2-1 grounding exercise

This grounding exercise is used as a coping technique against anxiety or by mindfulness enthusiasts. Although neither is the case for me, I noticed I’m a keener observer of my surroundings.

Notice in your surroundings:

- Five things you can see.

- Four things you can feel (touch).

- Three things you can hear.

- Two things you can smell.

- One thing you can taste.

Plus, this helps me get some of that attention back for my sensory memory. You can do this simple exercise during your short Pomodoro break.

One last word

We indeed live in a hectic (professional) world that demands a lot from us. Work piles up, and once you fall behind, you feel doomed.

All while hyper-productivity is preached from every pulpit. I got antsy if I wasn’t feeling productive. I pushed beyond what was expected of my body, especially when it came to sleep, and fell flat.

But during these past few months, as I was reevaluating my processes and systems, I would see a glimmer of hope. I could slowly lessen that mental overload as I was still going to work and working through my projects and commitments.

Resolve to test out one of these tips or strategies. Adapt them to your work context. But first and foremost, focus on sleep, nutrition, and exercise.

Again, this is task management for health’s sake.

First published on November 11, 2022.

Alexandra Martin

Author

Drawing from a background in cognitive linguistics and armed with 10+ years of content writing experience, Alexandra Martin combines her expertise with a newfound interest in productivity and project management. In her spare time, she dabbles in all things creative.