Have you ever experienced that sensation when you’re stuck in traffic on your way to an important job interview, and as time ticks by, it seems to accelerate? When every little second makes your heart race even more? Conversely, waiting in line for an hour can feel like an eternity.

Surely, an hour is 60 minutes, but it passes quickly when you’re in a flow state working on your dream project, yet that hour can also be unbearable when stuck in a meeting you could have easily missed out on.

This phenomenon is called subjective time, and it is an important concept in psychology, philosophy, neuroscience, and artificial intelligence. It’s not novel and has been studied in relation to consciousness, perception, and memory.

We make a big deal out of subjective time and time perception because we want to be productive. Studies show that our subjective feeling of having too little or too much time on our hands is damaging our mental health.

How did 2020, the year of the COVID pandemic, be such a mixed bag of feelings and perceptions? To some, time was unbearably still; to others, it flew by swiftly.

How do we assess subjective time?

I’ll focus mostly on defining the topic of subjective time, its relation to time perception, and how you can be conscious of it to make the most of your days.

What is subjective time?

Subjective time is mostly the experience of time, namely how individuals perceive and feel time. It is the personal, internal sense of time that is shaped by one’s thoughts, feelings, and experiences. It’s not bound by minutes and hours. Subjective time is often characterized by a sense of passage or flow, and it can vary significantly from person to person and from moment to moment.

In contrast to objective time, which is based on external measures such as clocks, calendars, and timekeeping devices, subjective time is a more subjective and personal experience. Subjective time is shaped by various factors, including one’s mood, emotions, attention, and memory.

Depending on your mood, for example, time may seem to pass more slowly when you are having a lousy day, are bored, or waiting for something to happen and more quickly when you are engaged in an enjoyable activity.

Emotions frequently dictate whether we experience time as passing fast or slow. Traumatic events, which come with intense emotions, can cause people to experience time in slow motion. This can lead to a sense of time slowing down or speeding up, depending on the intensity of the emotions involved.

Attention turns a passive activity into an active one. Paying attention and taking notes even in a seemingly boring lecture can make it more enjoyable and reduce its perceived length rather than passively listening and hoping for it to end. When you pay attention to the ticking clock, it’ll feel as if it is slowing down.

Fun fact: Time has a subjective duration only when you notice time. It is like a spotlight that can make time feel longer when we focus on it and shorter when we’re distracted away from it, such as being engaged in some fun activity.

Working memory is accurate with short intervals: it’s easier to estimate how long it took you to write an email than a whitepaper. Crude estimates or ‘guesstimates’ happen in the absence of a timesheet—they occur when you only have a rough idea of what you’ve worked on during the week instead of a clear breakdown of time entries.

Common experience shows how imprecise subjective estimates are, with people generally overestimating how well they did and how much they worked.

People perceive time differently. Let’s see how and why.

Time perception

Our brains process environmental information through various neural structures, including the frontal cortex, basal ganglia, parietal cortex, cerebellum, and hippocampus, to interpret time in fractions of milliseconds, seconds, and minutes.

The study of time perception is called chronoception, where psychologists, cognitive linguists, and neuroscientists study the subjective experience of time duration.

Simply put, your own time perception gives you an idea of how long an event or interval lasts based on your attention, mood, emotions, memory, expectation, and context.

It’s your own sense of how long an event unfolds in time. We could spend the same two hours at the movie theater—you could be bored out of your mind, and I deeply engrossed in the plot; you could be uninterested, and I excited about the hangout. Maybe you didn’t look forward to the movie as much as I did. Would you say our experiences and time perception were identical?

Bergson’s durée

René Descartes (1596–1650) debated the idea of time, Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) tried to provide an answer to the epistemological problem of time (read: “How do we know time is real and objective and not our own intuition?”), and mid-19th-century scientists, such as Gustav Theodor Fechner (1801-1887), conducted experiments to study the relationship between time as perceived and time as measured in physics.

French philosopher and Nobel laureate Henri Bergson (1859-1941) first discussed this subjective time flow in the early 20th century, which he termed “durée réelle” or “real duration”.

Bergson challenged the traditional understanding of time as a linear progression of discrete moments. Instead, he proposed the concept of “Duration” – a continuous and indivisible flow of existence, a subjective perception of time incapable of being sliced into measurable units.

He argued that “real duration”, or “experienced time,” is a dynamic continuum, with the past ‘bleeding’ into the present and the future.

“Real duration” means “lived time,” and is the time of our inner subjective experience. This is time felt, lived, and acted. This idea is intangible, particularly in a world that relentlessly measures, segments, and commodifies time.

Note: Objective time is necessary to get paid fairly and accurately. To this day, work is paid hourly, and time-tracking software is the norm in almost all digital environments.

Humans experience time differently than “objective time,” the scientific measurement of time, which is called the clock time. For Bergson, time is continual and subjective. As soon as we attempt to measure a moment, it is gone.

The strontium clock is the best example of “clock time”: it lags 1 second every 15 billion years.

This slavery to time distorts one’s perception, accelerating during busy periods and grinding to a halt during quieter times. It’s a constant tug-of-war between wishing time would speed up or slow down, leading to an oscillating relationship with time.

Subjective time in culture

Subjective time or “the lived experience of time” was the hot topic of high modernism in the early 20th century, when modernist English writers like Virginia Woolf, D.H. Lawrence, and Aldous Huxley wrote about their inner life shaped by durée. Bergson influenced well-networked figures like T.S. Eliot, Gertrude Stein, and Ezra Pound, who in turn disseminated Bergson’s idea of “Real Duration” to American writers, such as Faulkner and Robert Frost.

Virginia Woolf’s “Mrs. Dalloway” was initially titled “The Hours,” examining one day in the life of the protagonist. James Joyce’s “Ulysses” (the famous stream-of-consciousness novel reflecting inner monologue with no punctuation and improper syntax) wrapped the events of one day (19 hours, to be precise) in over 700 pages through the point of view of the two main characters. Here’s how you read stream of consciousness:

Read Ulysses’ tens of pages of stream of consciousness on Gutenberg.

The same one-day theme is found in Marcel Proust’s “In Search of the Lost Time,” a profound meditation on life, memory, time, and death. The seven-volume novel begins with “For a long time…” and ends with “Time.” It is recognized as the world’s longest novel ever written, spanning 1.2 million! words. That’s 9,606,000 characters. Enjoy Proust’s closing statement:

[…] I would therein describe men, if need be, as monsters occupying a place in Time infinitely more important than the restricted one reserved for them in space, a place, on the contrary, prolonged immeasurably since, simultaneously touching widely separated years and the distant periods they have lived through—between which so many days have ranged themselves—they stand like giants immersed in Time.

What about collective and personal histories? The macro and micro-narratives about some of the most significant days of our lives are usually interconnected.

According to a Pew Survey (2016), these are five of the most significant events of the last hundred years that happened in a single day:

- August 26, 1920: The 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote, established women’s suffrage in the United States.

- June 6, 1944: D-Day, the largest one-day military campaign in history, marked the beginning of the Allied invasion of Normandy during World War II, leading to the liberation of France from Nazi occupation.

- September 2, 1945: World War II officially ended with the unconditional surrender of Japan following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

- August 15, 1947: India gained independence from British rule, marking a significant turning point in the history of the British Empire and the emergence of a new nation.

- September 11, 2001: The 9/11 terrorist attacks took place in the United States, resulting in the deaths of nearly 3,000 people and marking a significant turning point in global security and foreign policy.

These are just five 24-hour events that had a profound impact on the world and significantly shaped the course of history. There’s a Holy Week or a year that changed history. I’m reminded of:

- 1600 BC: The beginning of Greek civilization, which was essential to Western heritage and the root of mathematics, philosophy, political thinking, and medicine.

- 5 BC: The birth of Jesus Christ has had a profound impact on the lives of billions of people and is the reason for the Christian calendar.

- 1776: The United States declared its independence, setting a precedent for other nations seeking independence and marking the beginning of the end of imperialism.

- 1945: The end of World War II, which ushered in a new world order and set the stage for the Cold War and beyond.

- 1969: The first humans walked on the Moon, marking a significant achievement in human history and the beginning of humanity’s expansion into the cosmos.

- 1989: The end of the bloc in Eastern Europe, signifying the beginning of the end of the Soviet Union and the fall of the Berlin Wall.

- 2001: The year of Windows XP release and Mac OS X release, marking a big revolution in computer and internet history.

- 2020: the most recent pandemic which brought world economies to a halt.

I’ve listed these dates and years to illustrate that while time flew objectively, the eventfulness of those days and weeks provided information and experience worth retelling for years to come. If you ask me, I’m still unsure what happened in 2020—it was such a blur, yet the year ended quickly.

If you ask people, the 15 minutes between the two 9/11 plane crashes is technically the standard duration of a daily stand-up or a shorter Pomodoro session, but every minute was anguishing. Solo climber Aron Ralston’s gruesome 127 hours (5 full days) stuck in Utah represent one month’s workload in objective time, yet the lived experience was excruciating.

How not to waste your days

Leaving history and culture aside, let’s segue into our normal, everyday lives.

I don’t mean to go dark and broody about memento mori (“remember you must die”), but Oliver Burkeman puts time into perspective – we have about 4,000 weeks to live, at best. His book serves as a reminder of life’s brevity and the importance of making meaningful choices in how we spend our time.

“Time you enjoy wasting is not wasted time,“ according to John Lennon. And there’s truth in this quote. We don’t want a hyper-productive life in which you cannot call a loved one because you could be working. We don’t want a hyper-optimized calendar that leaves no room to enjoy the sunset or a walk in the park.

Having said that here’s a handful of (non-)activities that are bad ways of wasting time:

1. Not having a goal or a vision for your life or career

It’s the French raison d’être (“justification for being”) that you know deep down, the Japanese ikigai (“reason to live,” the intersection between vocation and gifting), or a higher calling you feel compelled to pursue, which mobilized the likes of Martin Luther King, Mother Theresa, or Steve Jobs.

It may even be what the Nicoyans call “plan de vida” (“a reason to live”) that inspires purpose and optimism or the “pura vida” (“pure life”) of the Costa Ricans who promote a joyful, low-stress, and laid-back lifestyle.

Having a dream, a longing, or your life’s goal in mind doesn’t definitively mean you’ll achieve it, but without planning or foresight, your chances are closer to zero. Aim for the moon—you’ll at least shoot some stars. It’s OK to even set a few OKRs and try to make actionable steps toward them.

2. Doomscrolling

Doomscrolling, this punny term, refers to the overconsumption of negative news and information on social media platforms, which often leads to a loss of productive time and a negative impact on well-being.

Scientists have established that doomscrolling can lead to a loss of time awareness and a distorted perception of time, where users feel like they are spending excessive time on social media, even though objective time may not reflect this. This excess leads to feelings of guilt and frustration, having a negative impact on subjective time.

Plus, all the negativity of (fake) news or the overall uselessness of digesting too much news content isn’t conducive to productivity.

3. Excessive smartphone use

Smartphones are among the greatest distractions to focused work, study, or meaningful interactions, whether you are browsing social media, binge-watching, or playing video games. The constant stream of notifications, updates, and social media posts can be particularly addictive, as they trigger the release of dopamine and create a sense of anticipation and excitement.

The behavioral addiction to smartphone use is linked to dopamine, which can lead to a loss of focus on important tasks and responsibilities as individuals become increasingly preoccupied with their phones.

Plus, non-stop checking and scrolling can also lead to a sense of FOMO (fear of missing out), which can further fuel the compulsion to check the phone constantly.

4. Busy work on non-essential tasks

Not everyone will make a dent in the universe, and that’s OK (Burkeman’s quote), but busyness on tasks that do not contribute to your life goals leads to reduced efficiency. It can create unnecessary stress or frustration and an overall sense of unfulfillment. Time spent on tasks that do not align with priorities or contribute to meaningful progress will eventually feel like time wasted, leaving you feeling stuck or frustrated at the end of the day.

Cal Newport’s Deep Work is a great read if you want clarity around meaningful work in a distracted world.

5. Unnecessary meetings or social events

Not-so-shocking statistics (Treetop, 2024) on time wasted in unnecessary meetings show that around 24 billion hours are lost each year due to unproductive meetings in the U.S, and only 11% of meetings are considered productive, despite organizations spending about 15% of their working hours in meetings.

In a study by HBR, employees weigh in:

- 70% of employees say meetings are a waste of time

- 63% of meetings have no follow-up

- only 50% of the time in a meeting is spent on the agenda

- 71% of workers waste time every week due to unnecessary or canceled meetings

- meetings cost U.S. businesses $37 billion per year

Implementing strategies to make meetings more productive, such as having a clear agenda, inviting only essential attendees, and following up on action items, can help reduce time wasted in meetings. Have no-meeting days during the week, and be religious about keeping them.

Granted, you may not be in charge of these meetings, but you may reduce those social events that are clearly time-drainers. Resolve to having a number of social events, and politely declining the rest.

6. The procrastination you often feel guilty about

Procrastination is a complex, multi-faceted aspect that is linked to (time) perception. My insight into procrastination (having worked through it for the past decade) is that it relies on poor time management, skewed time perception, and wacky guesstimates.

What I’ve found recently is that my procrastination subsides when I challenge my assumption that a specific task will take “very long” (see below, “How to measure subjective time”).

Let’s say your ballpark estimate is that a task will take you 3 hours in the evening. You might be tired, so you’ll leave it for tomorrow. Challenge that assumption and start the timer or a Pomodoro app to see how long it takes you.

I’ve found repeatedly that the task isn’t as lengthy as I’d have thought and that I’ve wasted time putting it off.

Studies indicate that procrastination is also linked to people’s time perspective (I’ll delve into this topic soon). Individuals with a present-oriented time perspective, focusing more on the present moment and immediate gratification, tend to exhibit higher levels of procrastination.

On the other hand, individuals with a future-oriented time perspective, emphasizing long-term goals and planning, are less likely to procrastinate.

This connection between time perspective and procrastination highlights how one’s perception of time, whether oriented toward the present or the future, influences their tendency to delay tasks and engage in procrastination behaviors.

How to measure subjective time

We’ve established that subjective time is not directly measurable in the same way that objective time can be measured using clocks and calendars. However, some methods for measuring subjective time involve asking individuals to estimate or evaluate the duration of a particular experience or interaction.

Studies published in the Sage Journal or in the International Journal of Human-Computer Studies outline more methods. Still, the simplest way to measure subjective time is to ask users to rate their subjective experience of time using a 5-point Likert scale that ranges from “very short” to “very long” or from “very slow” to “very fast.”

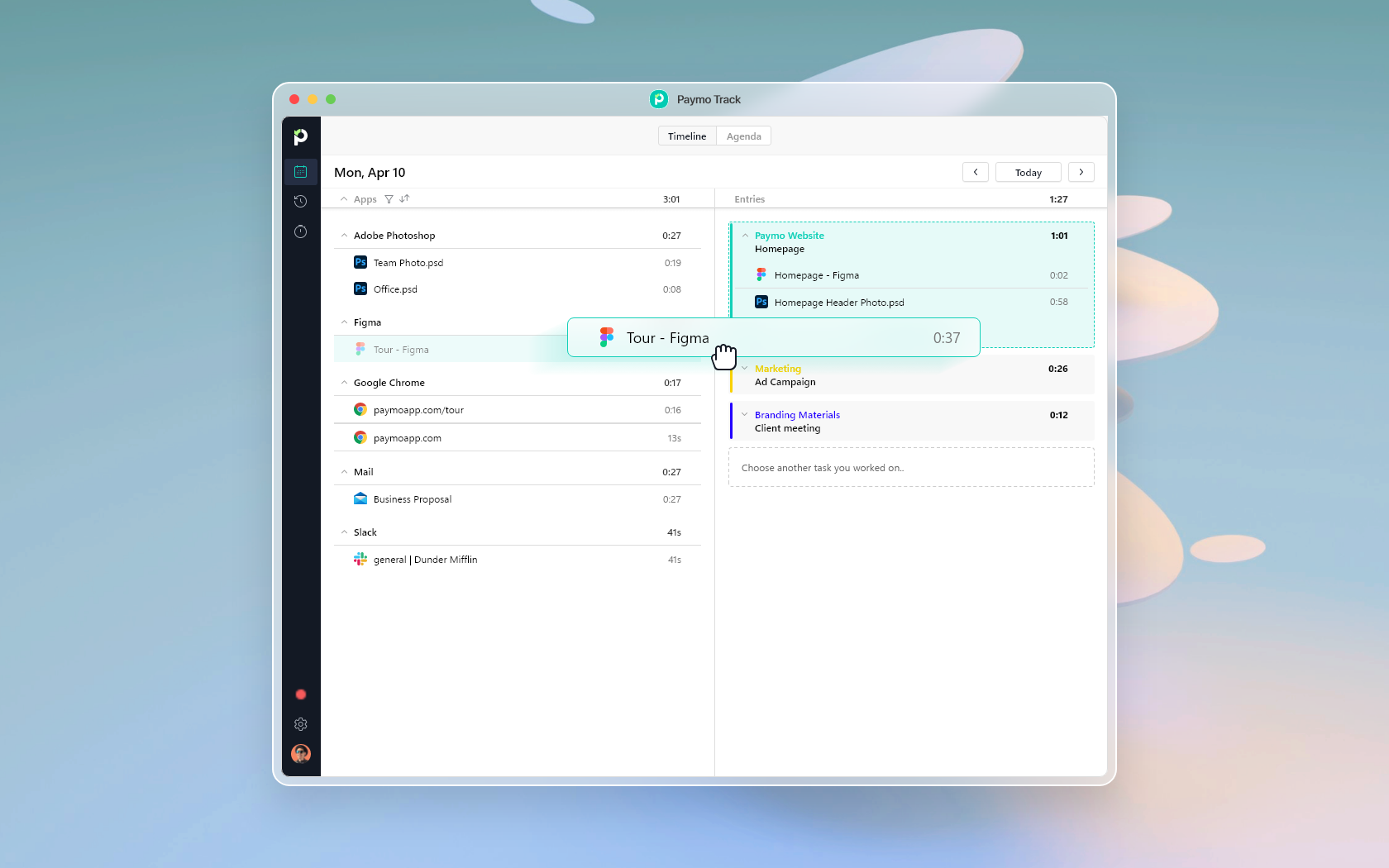

In Paymo Track, you can bundle activities under one task for a clearer picture of your projects.

Here’s a simple way to measure subjective time:

- During a regular workday, use an automatic tracker to record all your work activity (here’s how).

- For each task, write down how long you think it took and how slow or fast you perceived the task.

- Then, compare the estimated time with the actual time.

Paymo Track is a free automatic tracker for your desktop that’s easy to use and 100% private. Download Paymo Track for free.

Start tracking time with Pomodoro for free.

Conclusion

I’ve barely scratched the surface of Time, and although this thought-piece is peppered with academic disciplines, it’s important to stop for a minute and think about our lived time.

Some individuals can gauge the passing of time or determine the time of day with precision, while others struggle to keep track of hours slipping away.

If you aren’t naturally gifted with a keen sense of time, you can cultivate it. Learn how in my next piece, How to Fine-tune Your Internal Clock to Enjoy Life More (coming soon).

Alexandra Martin

Author

Drawing from a background in cognitive linguistics and armed with 10+ years of content writing experience, Alexandra Martin combines her expertise with a newfound interest in productivity and project management. In her spare time, she dabbles in all things creative.

Laurențiu Bancu

Editor

Laurențiu started his marketing journey over 18 years ago and now leads a marketing team. He has extensive experience in work and project management, and content strategy. When not working, he’s probably playing board games or binge-watching mini-series.